The following anecdote won't be as funny if I have to explain it. Hopefully you know/can surmise enough about architectural symbolism and Gauguin's personality/lifestyle to see the humor.

This is more-or-less an excerpt from tonight's dinner conversation:

M: So, I read this case study about the Eiffel Tower and modernity today, and I was surprised to find that Gauguin commented about the tower at the time of the 1889 exhibition. He said that he was impressed with the tower's...

J: [Interrupts] ...virility?

M: [Chokes on spaghetti while laughing] Ha ha ha!

[Recovers and clears throat] No.

J: [Chuckling and looking pleased about his clever remark] Then what did he say?

M: Gauguin admired the technical modernity of the tower; he called it a "triumph of iron."1 I am always surprised at how Gauguin really embraced modern life. On one hand, he wanted to be "primitive" and earthy by living in Tahiti and being a "savage," but really, at same time he loved modern life. It seems like he really embraced primitivism because it was the modern, avant-garde thing to do. He didn't want to be primitive because he wanted to get away from modern life - he wanted to embrace modernity by being primitive.2

---Don't you wish you ate dinner at our house? Then you could choke on spaghetti too. Don't get your hopes up too much though, because footnotes aren't included in our actual dinner conversations.

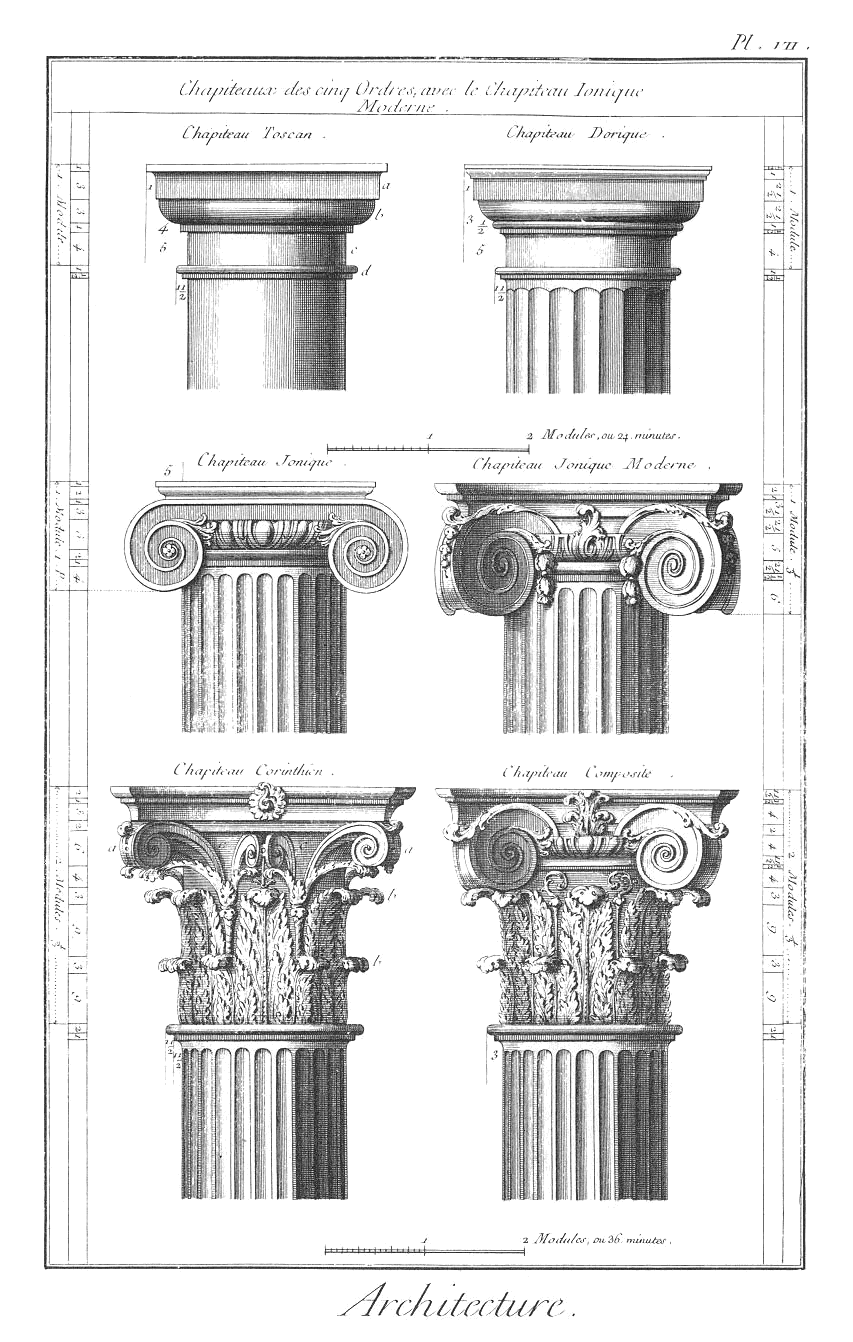

1 Gauguin admired the technical modernity of the tower, but he did think that the tower was designed with outdated decorative forms. This is the the full quote: "This exhibition represents the triumph of iron; not only regarding machines but also architecture. Though architecture is in its infancy, in that, as an art it lacks a sense of decoration proper to its own materials. Why, alongside this iron, so rugged and strong, is there trivial terracotta decoration? Why, next to these geometric lines or a wholly new character, this ancient stock of old ornament?" See Paul Wood, ed., The Challenge of the Avant-Garde (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 159.

2 During graduate school, I wrote a paper about how Gauguin was in a state of denial regarding his savage, primitive lifestyle in Tahiti. Even though Gauguin renounced modern civilization and claimed to be a "barbarian" in his writings, in actuality he couldn't part with modern life. For example, he was almost entirely reliant on tinned foods from the trading store in the area; he couldn't even bring himself to eat the native food! In addition, Gauguin frequently used oil paint when creating his art - a medium which not only is European, but also is closely tied to the art market, commodofication, and avant-gardism. In my opinion, Gauguin was "primitive" because it was the hip (ahem, "modern") thing to do. Gauguin's 1889 reaction to the Eiffel Tower solidifies my opinion that the artist was not leaning away from modern life before going to Tahiti (he arrived there in 1891), but leaning towards it.

.jpg)